This is a document I wrote in 2021. As such, my perspectives have changed. Nonetheless, I believe others may find value in it.

Defining Disability

Disability is defined in the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) as

DISABILITY.—The term ‘disability’ means, with respect to an individual—

(A) a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities of such individual;

(B) a record of such an impairment; or

(C) being regarded as having such an impairment (as described in paragraph (3)).

The reason for the implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) is because historically, disabled youth have been denied education.

Disability Models

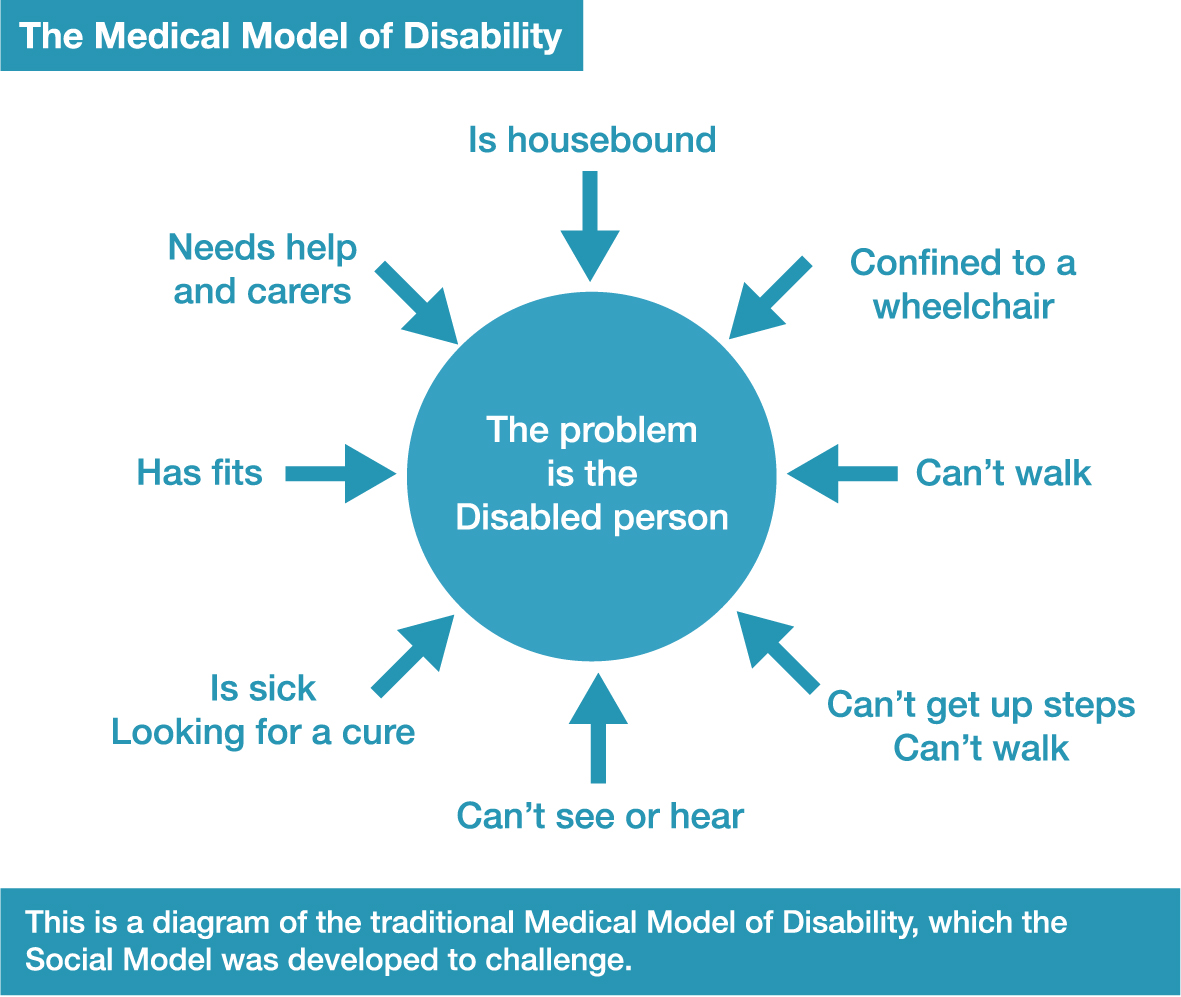

Medical Model of Disability

In the medical model, disability is perceived as an impairment in a body system or function that is inherently pathological. From this perspective, the goal is to return the system or function to as close to “normal” as possible. The medical model suggests that professionals with specialized training are the “experts” in disability. Persons with disability are expected to follow the advice of these “experts.” The language of the medical model is clinical and medical (e.g., left hemiplegia; partial lesion at the T4 level). This view is one that can sometimes be seen within the fields of health, mental health, and education.

The medical model of disability often is depicted in movies through a plot in which a disabled person is depressed and hopeless, but through friendship with an able-bodied person the disabled person learns to embrace life. A reverse twist on this is the idea that disabled people show able-bodied characters how to be better people.

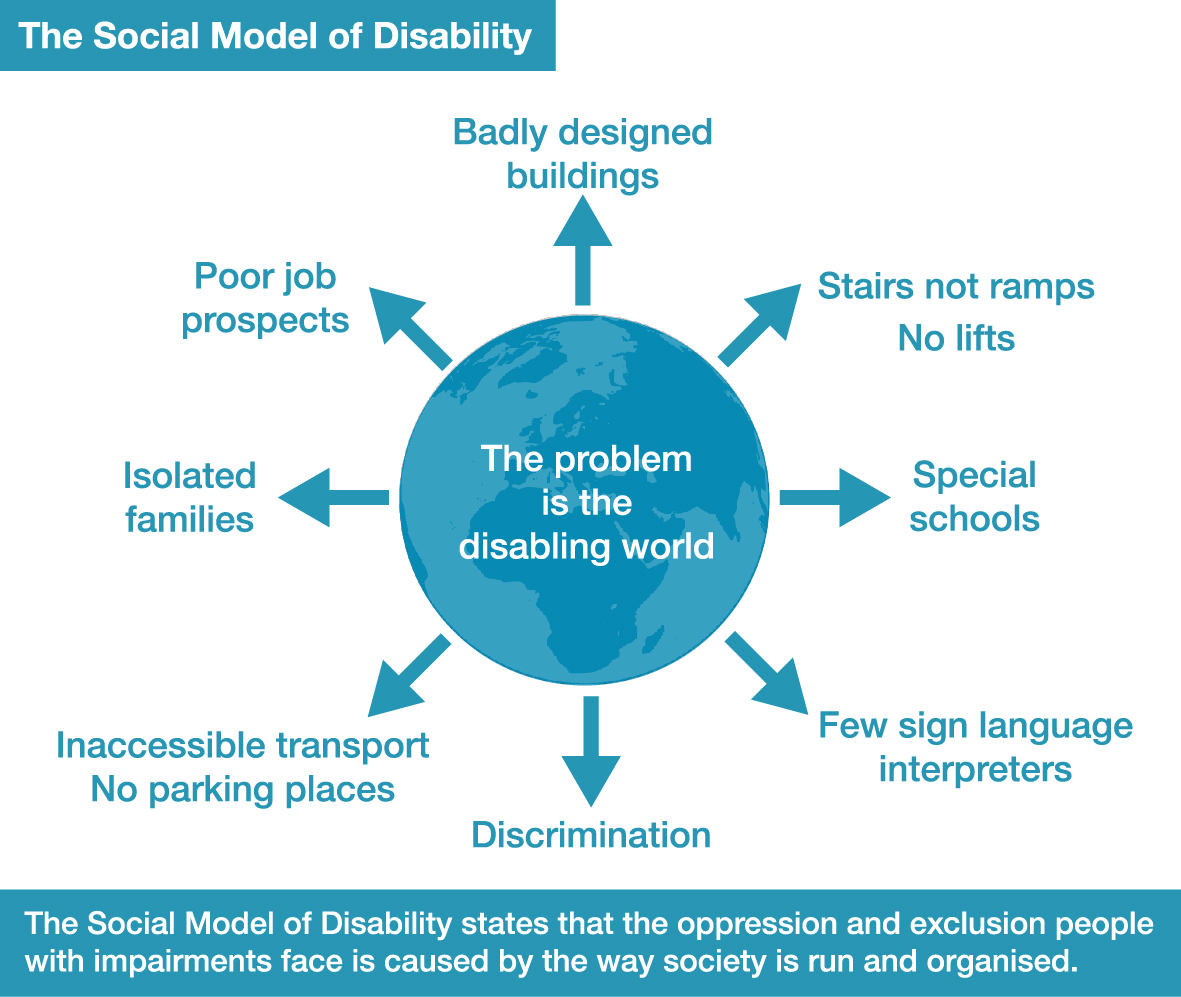

In the social model, disability is seen as one aspect of a person’s identity, much like race/ethnicity, gender, etc. From this perspective, disability is believed to result from a mismatch between the disabled person and the environment (both physical and social). It is this environment that creates the handicaps and barriers, not the disability. From this perspective, the way to address disability is to change the environment and society, rather than people with disabilities. Negative stereotypes, discrimination and oppression serve as barriers to environmental change and full inclusion.

Movies depicting disability from a social model are more apt to have multiple disabled characters who form bonds, learn, and grow, without dependence on an able-bodied character. Other films show disabled characters more realistically: in the context of loving families who are not ‘burdened’ by the disability; in a society that discriminates; as activist trying to change laws.

Students with IEPs are likely the subjects of the medical model of disability. This perspective focuses on how the disabled persons’ failings limit their ability to interact with the world. The social model counters this viewpoint by focusing on adapting the environment for inclusion.

To create educational and environmental equity, it is recommended that we accept the responsibility of accommodating all our youth. Accommodations should be led by the individual and include them in the process, otherwise they cannot be considered consensual and violate the youth’s autonomy.

Functioning and Support Needs

Different individuals require different support. Often we may use language to indicate whether someone has high, medium, and low support needs. It is worth noting that different individuals require different support in different situations and may fluctuate depending on the well being of the individual.

Additionally, many disabilities are not constant. It is important to recognize that most people have fluctuating needs. The medical model of disability does not accommodate for this and, to get support, many are required to frame themselves as their least capable self or even lower themselves to seem less capable. The perceived binary of disability built into systems requires people stigmatize themselves to receive care, and when the disabled individual shows themselves to be more capable, how deserving of accommodations they are is drawn into question. This dynamic has little to do with actual need or deservingness of access, although it heavily shapes our perception and approach to it throughout society and systems.

It is important to acknowledge that other identities may affect the perceived validity of one’s disability. Marginalized groups and those with low socioeconomic status may be resistant to acknowledging themselves as having limited capacity due to the struggle they are currently facing. You may hear people say that they may not be able to “afford” being disabled, can’t let it define them, or are not “disabled enough” to need help.

Obvious vs. Invisible Illness

If you cannot see an illness, you may not see the secondary costs of it. For visible disabilities, youth may struggle to have their agency and humanity recognized. The following is a contemporary understanding of what disability is.

Stigmatization of visible disability:

- Infantilization.

- No independence or agency.

- Obvious ableism.

- May receive stares.

- Cannot have ‘good days’ or do things that undermine what others’ idea of what disability is.

- People help without asking.

- Are not seen as worth investing in.

- Frequently abused and taken advantage of.

Stigmatization of invisible/transient illness:

- More effort goes into keeping up the façade of being nondisabled, likely to result in poor mental health and/or fatigue.

- Harder to get accommodations.

- Unlikely to be believed about disability and its impact.

- Must break down to be seen as disabled.

- Symptoms and disability dismissed.

Accommodations/Modifications

Accommodations are about changing the process to better fit the needs of the individual. Modifications adjust how we measure the individual’s success in the space. To clarify, accommodations affect access, while modifications affect process.

The following bullet points on accommodations and modifications is from Chaewanna B. Chambers:

Accommodations

- Process– change how the information is shared

- Product– change how they are sharing their learning

- Setting– change the environment

- Timing– change schedules

Modifications

- Changing tasks the individual is meant to do

- Changing the expectations of the individual

- Changing the curriculum to teach the individual

These are imperative for those who are disabled. Due to the perceived binary of disability and the additional effort that flexibility requires, accommodations and modifications must be fought for by those who require them. And yet, it would be remiss to dismiss the significance that accommodations have on those who do not have a disabled identity. Additionally, as explained above, due to systemic obstacles, those who are currently identified as deserving of care are not the only ones who need it. Accommodations and modifications are an equitable practice that allow all of us to show up and interact with the world equitably, and the process of establishing them builds relational ecology and an equitable culture.

It is important to discuss how and why aspects do not work. Different individuals have different needs and similar issues require individualized solutions depending on the individual case and experience. If an individual is having difficulty reading the expectations, why? Is their brain skipping over words? Are they mistaking different letters for each other? This will help point the way to a helpful accommodation or modification.

Accommodations are common, and yet modifications are typically only granted to those who are significantly disabled. This is incompatible with the variances of the human experience, as we all have different learning styles and ways of engaging with the world. By discussing our needs with each other, we can create a more flexible approach that improves the engagement of all.

Thus, we must be aware of the need for modifications and create flexible processes that may be changed depending on the needs of the individuals of we engage to create educational equity.

Discussing Them

We are experts of ourselves and of our own experiences. Everyone regardless of ability or disability will benefit from conversations about how they function in different environments and what accommodations would help them. Additionally, this allows us to acknowledge how the environments and spaces we exist in negatively impact our ability to operate within them and open the door to improving them.

Reasonable accommodations and/ or modifications help all of us come to the table with our best self and are key for equitable treatment of all, especially those with differing needs. When we invite someone into a process and/or space, we should ask them how they prefer to interact.

To begin this conversation, start with the space/process that you are inviting the youth to join. Go into detail. Access that you might take for granted, such as the money required for a train ticket or the ability to climb stairs, may be an obstacle for someone else.

- Where is the space?

- How do you access the space?

- What will happen in the space?

- What are the timelines?

These questions will help youth identify whether this space is accessible for them, and how to modify it for their inclusion. To address process, ask the following questions:

- What are the expectations of the youth while in the space?

- Who is a safe person to contact if there is a difficulty?

- Is this a sustainable agreement?

Once an obstacle to inclusion has been identified, we must engage the youth in conversation to identify why it is an obstacle and how that shows up for them. For example, if one was working with two youth who could not read the documents they were given, they each may have a different reason for having difficulty reading, even if they were both dyslexic. One youth may not be able to differentiate between letters because the characters are two similar—then I would find a font that has increased character differentiation such as Comic Sans MS or . The other student’s eyes may move faster than they can read the text, in which case the Arial font and increased text size may help.

As can be seen, it is imperative that we collaborate with the youth to create an individualized accommodation.

If one perceives difficulty, it is best to talk to the individuals one on one and ask about their experience with judgment. Psychologist Dr. Marshall Rosenberg has created a communication framework called nonviolent communication which provides guidance on how to have these conversations productively and without judgment, focusing on the individual and the situation. This communication framework—while vastly helpful and a trauma-informed practice—may trigger some with trauma or unique communication differences. In such cases, it is recommended that preferred communication is discussed.

Intersectionality

Historically oppressed groups are not only single-form minorities, and it is important to understand the historical context of the intersection of disability and other factors on engagement. This section serves to help you understand the systemic issues that may be at play in affecting educational equity.

Racism

Black, indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) are more likely to be disabled according to the CDC, and yet doctors are more likely to dismiss Black and brown people’s pain. According to the Berkeley Public Policy Journal, Indigenous mothers are dying at twice the rate of white mothers in America and Black mothers die at three times the rate of their Caucasian American counterparts. This is not a new phenomenon. Medical and systemic racism both have a centuries long history in America. Many of our great medical discoveries occurred through the subjectification and dehumanization of Black bodies in the name of science. It is important to recognize that this medical racism has shaped the Black communities’ relationship with health care, and justifiably so regarding the historical and contemporary realities of medical racism.

Trauma

Research about adverse childhood experiences show that childhood trauma are correlated with mental and medical health problems that are correlated with disability. Thus we must be aware of disability in order to implement equity for marginalized groups, who are both more likely to be disabled due to trauma and systemic inequity and less likely to be identified and supported as such.

Those who have a low socioeconomic class are also likely to face systemic barriers to health care and diagnosis, prohibitive costs being the primary among the obstacles. Additionally, accessibility is associated with increased cost due to assistive technology and increase resources required to support access, which is untenable for the vast majority of Americans.

Gender

Girls are socialized to behave differently, and as such they are less likely to be identified as being neurodivergent. Their pain is also frequently dismissed, as is that of Black and brown youth.

Examples of Accommodations

Contact Special Education for recommendations, and take a look at the Job Accessibility Network‘s website for more ideas. As previously stated, every individual has their own needs, and prescribed accommodations cannot and should not replace a collaboration to find a solution that works for them.

- Add white spaces between letters to improve readability.

- Have alternative text for images on websites, digital documents, and in emails.

- Create difference in different sensations such as texture and smell to increase navigability and agency within space.

- Youth that click at regular intervals may be doing so for echolocation. Allow them to do so.

Hearing Impairments

- Ask youth with audio processing and/or language difficulties what sorts of accommodations would be helpful.

- If the youth signs, provide an interpreter who signs in their language. Have teachers and students how to sign to support inclusion

- Closed captions for video calls and conferences—Google Meets provides this service without the requirement of an interpreter. Automated captions, while cheaper, are often inaccurate. CART is a better alternative.

- Youth may read lips. In such a case, look directly at them so they may clearly read your lips.

- Make sure your mouth is visible, and understand that lip reading is an art. Additionally, youth who read lips may not always have the energy to do so.

- If they are deaf in one ear, they may

- Be overwhelmed by sound (check the sensory processing section)

- Not know where sound is coming from

ADD/ADHD

- Communication difficulties

- Give them 10 different tasks to switch between or 1 task to focus on in a space without distraction.

- Which works best depends on the type of ADHD or ADD.

- Each individual has their own ideal level and kind of stimulation.

- Chattiness is a healthy outlet for hyperactivity.

- Special interests.

- Work with them rather than trying to get them to work with you. Explaining why is very helpful.

Autism

Autism is a pervasive developmental disorder characterized by multiple areas that may be affected. Additionally, it is characterized by extremes, and can be typical in many different areas. For more information, please read this comic.

- Understand communication difficulties are equally on your side as they are theirs and adapt accordingly.

- One person with autism is just one person with autism.

- Work with them rather than trying to get them to work with you. Explaining why is very helpful.

Chronic Illness

- Understand pain is exhausting and accommodate for that.

- Read this anecdote to understand fatigue.

Learning Difficulties

- Communications in Plain Language

- May affect processing of different information.

- They are perfectly capable; it may need to be approached differently.

- Sometimes processing takes slower.

- Arial font is the easiest to read for many, although fonts such as Lexie Readable have differentiation in each letter that is also helpful. It depends on how the individual’s brain processes the written word. Additionally, research shows that the individual size of each character improves legibility.

- Larger size letters

- Prone to frustration.

- If they hit a wall, it may be helpful to switch gears for a bit.